The breeze had picked up, the moon high in the sky and the little fire on the beach was blessedly warm. The older gentleman spoke softly, a gentle lilt to his voice as he retraced the history of Fire Island and the Fire Island Lighthouse. “There seems to be some disagreement about how Fire Island […]

Tales From Head of the Harbor and St. James I: New Thoughts on Mary Hatchet and Mary’s Grave

Top: Mary’s Playhouse at Head of the Harbor. Mary lived with her father in a large rambling house on Stony Brook harbor, in what is today known as Head of the Harbor, New York. One can assume that Mary’s father was anticipating a large family, or perhaps more likely, he inherited the house. But either […]

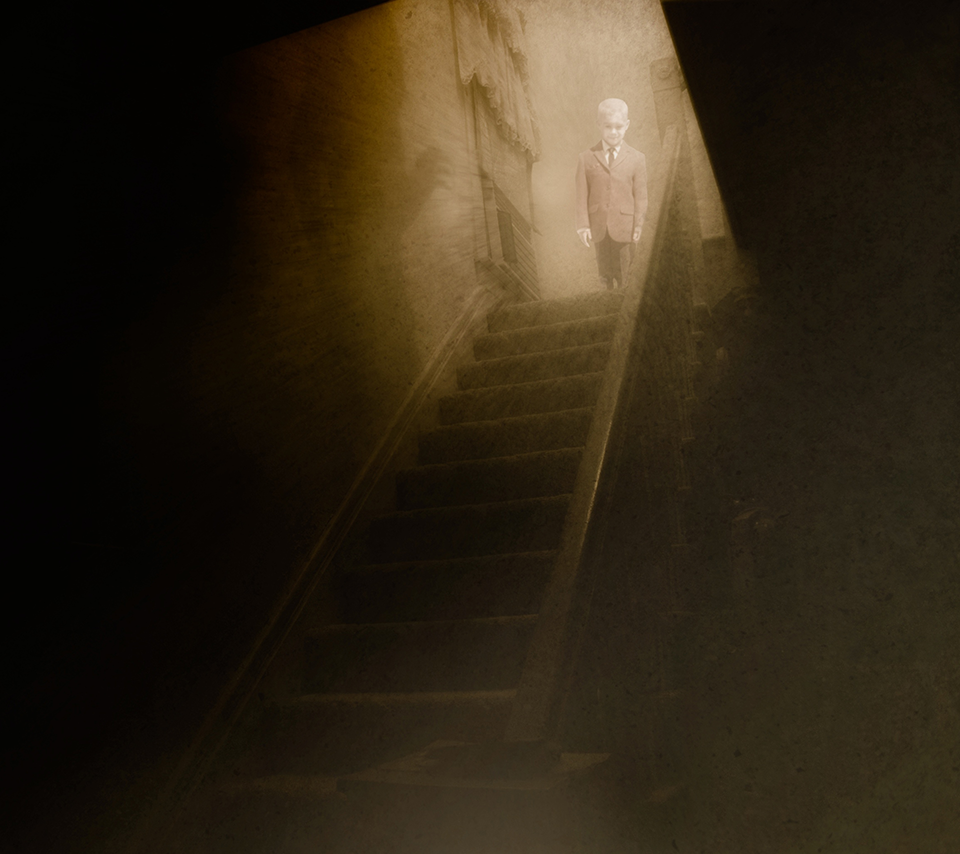

Tales of Old Stony Brook I: The Haunting of the Stony Brook Grist Mill

When a building becomes a part of a person’s life, there’s a better chance that it will become haunted. This only stands to reason. The more people who are touched by a building, the better the chance. Is this not so? One of the centers of colonial life and the years that followed was the […]